Great Japanese home handicraft & antique shopping in Japanese!

The Japanese handicraft & antique world's are big & unique! Few countries in the world have the range of living handicrafts that Japan does. Italy comes close, for sure. And so does China and probably Bali too! It isn't easy to keep old traditions & techniques fresh and relevant in modern or contemporary times. In fact, it is a matter of survival or adaptation. And only the smart and still relevant crafts survive in Japan or anywhere else.

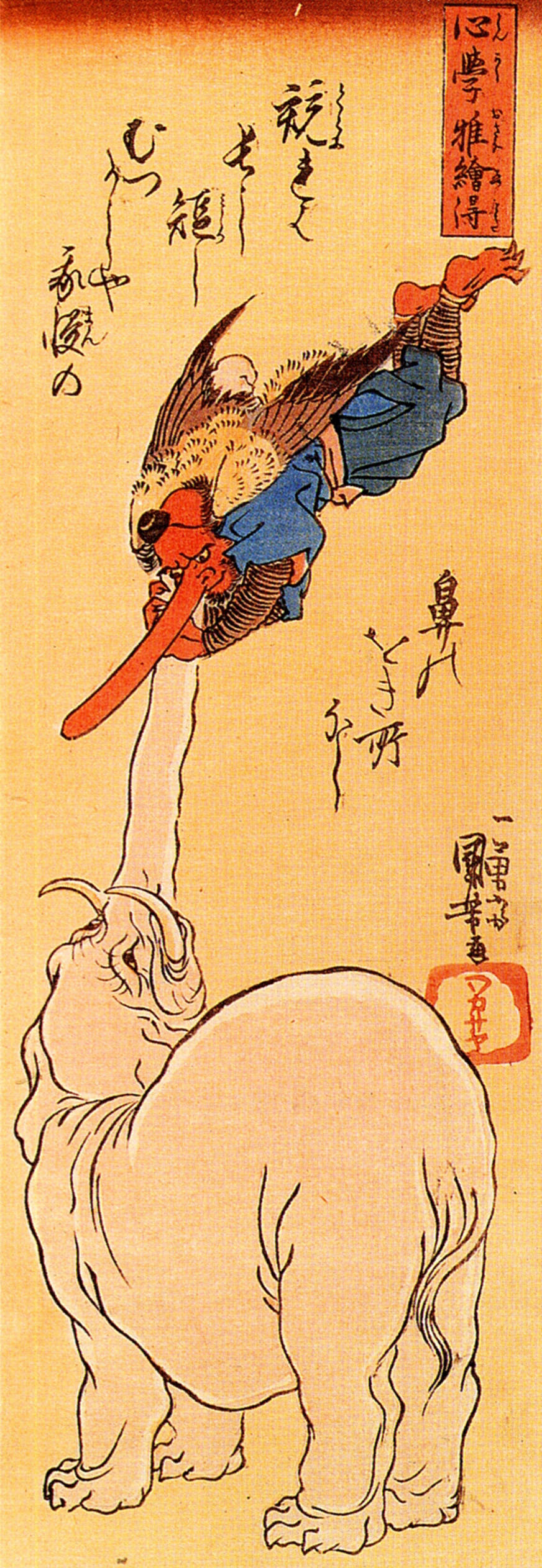

And if you are looking for old handicrafts, antique handicrafts then the spend is higher but so is the prize. Japan's amazing antiques, from furniture and ceramics, to woodblock prints and textiles, are well worth the price! Learn more!

The main topics discussed in this post are traditional Japanese handicrafts for the home and kitchen & Japanese antique shopping expressions you will need:

- Japanese crafts for the kitchen from the simple things to the exotic must have tools

- Japanese antique shopping expressions in easy-to-understand Romanji English

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!

Quality Japanese crafts for your home & kitchen

Japanese crafts are often regarded to be formal and for special occasions only. But this is not true. Just as many handicrafts are simple, inexpensive and created for everyday life. And even simple, daily-life things are skillfully and patiently created by Kyoto craftsmen, who pride themselves on making beautiful things that last for a long, long time. Here are three accessories that you are sure to find useful.

Lacquerware soup bowls: New black or dark red lacquer tableware is expensive. But Kyoto’s Uruwashi-ya offers you a great solution: used lacquerware. Used or antique lacquerware is very reasonable. However, you should enquire about how it will hold up in dry climates, because lacquer is ideally suited to high humidity environments.

Brushes & brooms: Need a handmade brush or broom to clean the house or your garden? Then you’ve come to the right place. Naito Shoten an early 19th-century handmade brush and broom shop in Kyoto has everything you could possible want. Everything from large to small, including brushes for long glasses, pot cleaners, and mats (from ¥400). On the north side of Sanjo, just west of the Kamogawa River. Open daily 9:30-19:00. Tel: 221-3018.

Japanese Washi paper table decorations: Warm to the touch and naturally colored, Japanese handmade paper or washi can easily be adapted to serve as a table cloth, coasters, and for all kinds of other table decorations. And best of all: washi is so strong that it can be used over and over. For a great selection of washi, go to Kamijikakimoto, on the east side of Teramachi, about 100 meters north of Nijo. Tel: 231-1544.

Kasa Umbrellas: An umbrella is the perfect companion on your strolls through the city. Of course you can find any number of designer and cheap plastic models to keep a fair bit of you dry. But why not get a really nice umbrella that you can use at home as a reminder of Kyoto. Nothing can be more beautiful than the handmade umbrellas of Japan, a skilled tradition that goes all the way back to the dawn of civilization. Though the umbrella was undoubtedly an invention that came from the genius of Chinese civilization, Japanese umbrellas have over the centuries taken on a design and style all of their own. And what stunning colors to choose from!! For that perfect umbrella that will last forever and makes the perfect gift, pay a visit to Kasagen in the Kyoto's Gion geisha district. Since 1861, Kasagen has been selling the finest quality handmade paper umbrellas — large ones (bangasa), delicate ones for the ladies (janome), and, for later in the season, hand-painted sun parasols (higasa). Kasagen: 284 Gion-machi, Kitagawa. Higashiyama-ku. Tel: 561-2832. Open daily 9:30 am - 9 pm. Closed on national holidays.

Sensu Japanese fans: Though the air conditioner serves to comfort us these days from the often humid heat of summer, there was a time when the fan was the best one could hope for in getting relief. The hand-held fan has long been a sophisticated symbol of the Orient. It could be opened with a flourish to make a point or indicate indifference, or be used to point at something or someone. Usually an accessory for the ladies, Japanese fans or sensu, which are of the folding type, come in a wide range of styles and designs. They can be expensive or very cheap, but either way the materials used to make them are all natural and for the most part they have been hand crafted in some way, if not entirely. Naturally, sensu make a fine gift that is easy to carry around and of practical use on a hot summer day anywhere. The most famous fan shop in Kyoto is Miyawaki Baisen-an, which is located in the old part of the downtown area just a little southeast of the Oike-Karasuma subway station and intersection. The store has been in business since 1823, and is a delightful place to visit for its fine collection of lacquered, scented, painted and paper fans, and also for its old-world atmosphere. Stop in and have a look around. You’re sure to find something that you will treasure and probably use. Miyawaki Baisen-an: Tominokoji-nishi iru, Rokkaku-dori, Nakagyo-ku. Tel: 221-0181. Open daily 9 am-5 pm.

Japanese Incense: Incense floating on the breeze can cause you to stop and momentarily forget everything, as if you had entered a brief but sweet Zen meditation. A wonderful tradition of the far east, incense fragrances differ from country to country. Most famous in the incense world is probably the sweet and heavy smells of the Indian subcontinent, which have been widely available around the world in a bewildering range of shapes, styles, and smells for many years. Japanese incense is less known and more expensive, but once you smell the subtle and soothing fragrance of Japanese incense you are sure to be hooked forever. The Japanese hardly use incense in their homes; it is something of the seemingly aristocratic and sophisticated world of temples and shrines, and perhaps tea ceremony houses. But that doesn’t mean you can’t buy some. In fact there is no end to the shops which sell incense. However, if you are looking for the very finest, which means 100% natural, then there are only a few major shops to choose from. If the incense you see in a shop is brightly colored chances are that it’s not entirely made of natural ingredients. The best incense is usually tan brown or light yellow. Just ask the shop keeper (kore wa junsui no oko desuka?). As far as shape goes there are several styles to choose from: slim coils, small sticks, chips, coarse powder. The chips and powder are sprinkled on burning charcoal. Another thing that is special about the finer Japanese incenses is that even after they have burned away the smell lingers in the room for quite a long time. Give your nose something to look forward to. Buy some incense and take it home — it’s worth it!

Kungyoku-do: Opened originally as an herbal medicine shop in 1774, this store now specializes in incense. They also stock a wide selection of brushes for sumi-e (ink painting), ink sticks, handmade paper and tea ceremony utensils. Open daily 9 am-5:30 pm. Closed the first and third Sunday of each month. Nishi-Honganji-mon-mae, Horikawa-dori. Shimogyo-ku. Train and Subway: Kyoto Station. Bus: 9, 75 to Nishi Honganji mae. Tel: 371 0162.

Geta geisha sandals: In English the distinction is made between footwear and footgear. Japanese geta, or wooden clogs definitely fall into the latter category, working as tools rather than casual wear. Protecting the feet as well as improving work efficiency, geta have been serving Japanese feet for quite a long time.

Geta appear to have been invented in the Yayoi period (200 BC - 250 AD). Called ta (paddy) geta, they were basically wooden planks strapped to the feet to keep the farmer out of the muck. Geta (along with the kimono) really hit their stride in the Genroku period (1688 - 1704) when styles proliferated. The fashionable inhabitants of Edo (present day Tokyo) liked their geta narrow and tall, with long thick throngs -- to make their feet look slim. Light, strong, and beautifully-grained, kiri (paulownia) was, and still is the wood of choice.

There are countless kinds of geta, but they roughly fall into two basic categories: reshi or masa-geta, which are made from one block of wood, and sashiba-geta, which have teeth -usually of a different and harder types of wood. It is said that high quality geta have a close, even grain -- the more lines, the better. Good geta can cost as much as Yen 60,000 at traditional shops where they are hand made. However, at the shops listed below, prices are around Yen 2,000.

Of course, geta go with kimono or yukata. No tabi (Japanese socks) are needed -- just wear them with naked feet and listen to the sound they make -- kara koro, kara koro, kara koro..... Kyoto Handicraft Center: On Marutamachi St, north of Heian Shrine (See ad on back cover) Yukata and geta are found on the 2nd, 4th, and 7th floors. Tel: 761-5080. Sanjo Tanaka: On the south side of Sanjo St, west of Kawaramachi St. Tel: 221-1011. Rakumi: On west side of Shinkyogoku St, south of Sanjo. Tel: 231-2924.

Misu and sudare bamboo blinds: Traditionally, the Japanese overcame the soaring temperatures of the summer by shielding their windows with reed, rush, or bamboo sunscreens, known as sudare. Unlike Western blinds, sudare, allow the air to circulate. Besides keeping the temperature down, sudare filter light into the room turning it almost amber.

Sudare's predecessors were exquisitely-crafted brocade-trimmed bamboo blinds called misu, which developed alongside Shintoism. Their original function was to create a physical separation between the sacred inner sanctuary occupied by the gods and an outer area to which ordinary people were admitted. They were also used to define and enclose the sacred space occupied by the Emperor. Towards the middle of the Edo period, however, rich merchants began to use misu in their own homes for more practical purposes — to provide protection from the sun. Used for such secular purposes, these blinds became known as sudare.

Making these blinds, which are common on the outside of Kyoto's historical machiya townhouses, is a time-consuming process. One person can split enough bamboo to make four sudare or misu in a day, which in turn will take one person a day to sew, and one person a day to finish by stitching on the decorative brocade. First the bamboo is cut and set aside for about a year to allow it to season. Then it is cut into more manageably-sized pieces, boiled in a sulfur solution, and allowed to dry. This process is repeated a number of times until the bamboo has absorbed enough of the sulfur to repel insects and to have taken on the right color. Sometimes, if a darker color is desired, the bamboo is dyed with a natural dye, such as tea.

It is no doubt this final labor-intensive process that makes bamboo sudare so expensive. The standard size for an indoor sudare is 96 cm by 172 cm (to suit Kyoto-size tatami, which are bigger than average) and they cost from ・150,000 to ・200,000. Usually four sudare are used together, so fitting a room out with these blinds is something of an investment, although they will last a lifetime. If the blinds are kept well-dusted, they should last for up to eighty years." Misu make use of flat sections, so the final rounding or squaring off process is not necessary, a saving of time that is reflected in the cheaper price. A misu about the size of one tatami mat costs ・35,000. A two tatami mat sized one costs ・50,000. Maeda Heihachi Shoten, on Teramachi, south of Shijo, is open from 9 to 6, except on Sundays and public holidays. Tel: 351-2749.

Bamboo Crafts: Kyoto, known as the “bamboo capital of Japan,” has produced a wide range of bamboo crafts for centuries for the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and several other traditional industries. The simplicity, strength, easy workability, and relatively low cost of bamboo has made it a part of Japanese daily life for more than 1,000 years. Onoe Bamboo shop, on the north side of Sanjo west of Higashioji, has a wide selection of bamboo items including common household goods at reasonable prices (closed Sunday mornings). Tel: 751-0221. The Nakagawa Bamboo Shop offers 2-hour courses in bamboo baskets (groups only, advance reservation required). The shop is located on Gokomachi, north of Nijo. Tel: 231-3968. Tenugui Textile Art: Tenugui, unhemmed pieces of printed cotton cloth, about thirty-two centimeters wide and ninety-three centimeters long, come in a variety of colors, patterns, and designs, from the bold and simple to the traditional and sophisticated. At the end of the Edo period, tenugui were an indispensable fashion accessory. For the traveler, tenugui are especially useful, as a neck scarf, as a head covering, or as something to frame on the wall. Eirakuya Hosotsuji Ihe Shoten sells an amazing collection of new tenugui print designs from the early part of the 20th century. If you are looking for an interesting gift check out the tenugui (¥1,000-¥1,800), bags and tapestries here; on the east side of Muromachi, south of Aya-koji; 11:00-19:00, closed on Mondays; Tel: 256-7883. Japanese Paper Lanterns: Traditional Japanese paper lanterns are made to last for a long time. Light and easy to carry in your take-home luggage they make a perfect gift or memento. Miura Shomei specializes in hand-crafted paper lanterns. From around ¥4,000. On the north side of Shijo, west of Yasaka Shrine. Open 9:20-20:00, closed Sundays. Tel: 561-2816. Tsujikura sells various kinds of chochin lanterns, from cute little ones to expensive ones for interior decorators. On the east side of Kawaramachi, north of Shijo. Open 11:00-21:00, closed Tuesdays. Tel: 221-4396.

Nabe Hot Pots: in the winter months the Japanese love nothing more than cooking up all kinds of things in communal (like fondue) nabe pots. These sturdy, wide-more-than-deep ceramic pots are a great thing to take home. They are usually decorated with traditional seasonal motifs (often cherry blossoms: something to look forward to during the cold winter months). If you do get a nabe, you should get a portable gas burner so that you can place it on your table at home and the whole family or friends can eat together. Japanese Winter Hanten Coats & Vests: the Japanese don’t have central heating. Instead portable kerosene heaters are used in almost all homes and apartments. Blanket-covered heatlamp table (kotatsu) are also a winter favourite. But if you have to venture outside, into a cold room, or just want to stay extra warm, traditional padded (wonderfully patterned) hanten coats and vests are the way to go. Look good and be extra warm this winter: get a hanten! Traditional Hot Water Bottles: getting into the cold futon on a bitter cold night is always a bit of a shock. That’s where a ceramic bottle of hot water (usually placed at the foot of the bed) comes in super handy. Called yutampo, they were are traditionally made of thick, light-weight metal. Unfortunately, the old ones are not so common any more, but if you look real hard you should be able to find one (ask at local pharmacies; if they don’t have one they can tell you where to get one; plastic ones are widely available at big department stores).

Useful Japanese expressions for antique shopping

Japan's many antique markets, at Buddhist temples & Shinto shrines, are the best place to buy old things. Often really old things for next to nothing! Every year countless of ancient Japanese estates go to auction. Frequently, the younger generations have little interest in their parents' or grandparents' stuff. So, all those old and really valuable artifacts flow into the "flea markets." Kyoto has two really big ones each month: 1. The 21st at Toji Temple (one of the oldest in Japan). 2. On the 25th at Kitano Tenmangu Shrine, a Shinto complex that boggles the mind!

In Tokyo there are regular markets as follows: Oedo Flea Market at the Tokyo International Forum Building, one Sunday a month; United Nations University Farmers' Market, weekends; Tomioka Hachimangu Antique Market, twice monthly; Setagaya Park Flea Market, three times a month; Yoyogi Flea Market, monthly; Oi Racecourse, almost every Saturday and Sunday, the nearest station is Oi Keibajomae on the Tokyo Monorail.

Remember, the really valuable antiques are quickly separated from the mass flow coming out of the old homes of the elderly and go to high-end antique stores in Kyoto and Tokyo. In the best shops, everyone speaks English. But in the best shops expect to spend hundreds of dollars not tens of dollars, OK? Learn more!

And here is the Japanese you will need when bargaining for antiques at the markets or in the higher-end antique shops of the country. Good luck! And never give up!

Antique: kottouhin

What is this for? Kore wa nanini tsukauno desuka?

How much is it? Kore wa ikura desuka?

(It is) XXXX yen. (Kore wa) XXXX yen desu

Can you make it cheaper? Motto yasuku narimasen ka?

How about XXXX yen? XXXX yen deha dodesuka?

How old is it? Kore ha odregurai furui mono desuka?

I'm just looking. Chotto miteru dakedesu

Can I touch it? Sawatte mo ii desuka?

Do you have anything similar to this? Kore to onaji mono ha mou hitotsu arimasu ka?

How old is this? Kore wa dore gurai furui deska?

Edo jidai (1603 - 1867); Meiji jidai (1868 - 1911); Taisho jidai (1912 - 1927)

What is this made of? Kono sozai ha nan desuka

Wood: ki: Sugi: cedar; Cypress: hinoki; Sakura: cherry; Bamboo: take; Metal: kinzoku; Silver: gin; Copper: do; Brass: shinchu; Iron: tetsu; Cotton: men; Silk: kinu; Linen: asa

Is it fragile? koware yasui desuka?

Can you pack it and send it to me ? Konpō shite okutte itadakemasu ka?

- Japanese crafts for the kitchen from the simple things to the exotic must have tools

- Japanese antique shopping expressions in easy-to-understand Romanji English

- Indexed full list of all my blog posts | articles.

- Indexed full list of all my Japanese culture essays.

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!