Yuzen dyeing, stones for gardens, woodwork, pro lute musician interview

Wishing the world a solemn goodbye to 2024 and a hopeful note for 2025. Japan will continue to be an extremely popular tourism destination. Most foreign travelers to Japan, 70%, will stick to the famous cities of Japan and what's near them. This post covers yuzen textile dyeing, the special sands and stones used for gardens, a peak at Kyoto's woodworking industry, and an interview with a professional biwa lute musician.

Before you get to the index leading to all this content, I would like to say that travel, local travel, regional travel and international travel requires a certain level of etiquette and a bit of foreign language effort. I have been very impressed in this regard with Scandanavians and Germans and Austrians on my travels across Planet Gaia (1976-2025). They learned 10-20 keywords or phrases; knew the main taboos and religious mistakes to avoid. And kept their voices down and tried to blend in. Bad tourists don't do any of these things. In 2025, I would ask you to do the same in Japan and also to tell your friends that "good behavior" is right behavior when traveling and in pretty much all other situations. American politics aren't about red or blue. Politics are about rigth & wrong, and what's good for everyone not the few. Thank you! Ian Martin Ropke . . .

- Kyo Yuzen natural dyeing creates strong beautiful textiles

- The best granite & sand in Japan for gardens

- Kyoto's woodworking industry

- A Conversation with a pro biwa lute musician

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!

Kyo Yuzen natural dyeing creates strong beautiful textiles

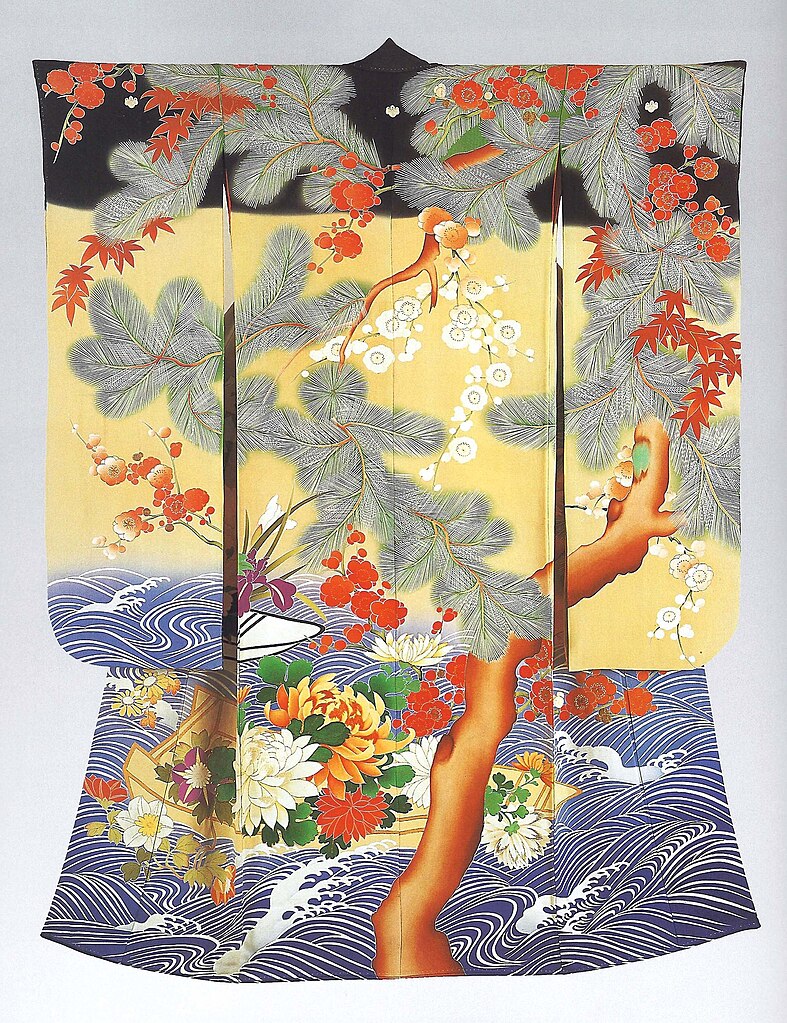

For centuries, Kyoto has produced some of the most beautiful and prized textiles in the world. Kimono made with the kyo yuzen dyeing technique are among the most prized of all. These exquisitely designed, hand-painted fabrics are produced entirely by hand.

Kyo yuzen as it is known today is the genius of one man: the 17th century artist Yuzensai Miyazaki. Miyazaki began his career as a fan painter and applied the skills learned in that craft to develop new and innovative techniques and pigments for textile dyeing. Miyazaki opened a shop in front of Chion-in Temple (at the north end of Maruyama Park, NE of Gion) in 1687, and his unique designs soon made him famous throughout the country.

Yuzen dyeing is mostly done using natural plant or mineral pigments and silk crepe. The patterns are either drawn by hand, or traced from a stencil. In both cases, the artisan uses starch made from rice to blank out those parts of the fabric which will not be dyed in a technique very similar to that used in batik, or wax-resist dyeing. Once the dye has been applied, the cloth is steamed to make the dye fast. These steps must be repeated for each color. Even when using stencils, it is a laborious process-a typical fabric for a kimono can often have 50 or 60 colors. For an elaborate furisode kimono, worn by young women on very formal occasions, over 700 stencils are used, and even everyday kimonos on average require over a hundred.

For more about yuzen or textiles visit: 1) Kodai Yuzen-en: yuzen silk dyeing demonstrations; on Takatsuji, east of Kuromon; Tel: 823-0500. 2) Nishijin Textile Center: Nishijin textile center; west side of Horikawa, south of Imadegawa; Tel: 451-9231. 3) the expansive Kawashima Textile Museum in north Kyoto. 4) The stunning Kubota Itchiku Art Museum on Lake Kawaguchi facing Mount Fuji NW of Tokyo. 5) The permanent collections in the national museums of Nagoya, Tokyo, Kyoto and others.

.The best granite & sand in Japan for Japanese gardens

Japan is famous for its stone and woodwork. Some of the Japanese techniques for creating things with stone and wood are unique and can not be found anywhere else in the world. When it comes to stone, some of these of these techniques can only be found in Kyoto.

The Japanese having been carving and working with stone since the Nara period (710-794) when Buddhist symbols and iconography came into great demand all over the country. In the beginning, as with any new craft form, the results were rough. However, the discovery of excellent granite in the village of Shirakawa, at the base of Mount Hiei (the giant peak that looms large over Kyoto to the northeast), Kyoto stone carving became the finest in the land.

Today, the tradition continues. Kyoto is home to over 80 firms (with a total of nearly 400 employees) that specialize in stonework. Eleven Kyoto stone craftsmen are recognized by the national government as Master Craftsmen. The tools of the stone mason are quite primitive and the work is very hard. Basically, they use heavy iron hammers and chisels and a lot of sweat.

Shirakawa granite works are particularly common in high-class Japanese gardens. It is used for large lanterns, square blocks enscribed with Sanscrit characters, Buddhist figures, or geometrical patterns. In particular, the birth of Japanese tea, in the Momoyama period (1568-1600), resulted in a dramatic increase in the production of tall stone lanterns for traditional gardens.

Shirakawa gravel and sand are also prized in garden design for a number of reasons. If the sand is too fine, it will blow away. If it is too heavy it prevents design fluidity and lets too much moisture to escape. The Kyoto Shirakawa sands and gravels are perfect. The sand grains are of the most desirable color (weathered white or gray granite) and size (about five millimeters in diameter).

Two excellent examples of Shirakawa gravel and sand can been seen at the sub-temples within the Daitoku-ji Zen complex (especially Daisen-in) and the raked sand and gravel landscaping at the Silver Pavilion. With a little imagination, you can feel the waves of the sea and see the currents that would whirl around a tiny boat.

Some of the best places to see these stones and the stone quarries they come from are along the Shirakawa Stream on the road leading up to the top of Mount Hiei, within walking distance of the Silver Pavilion or just a min fare cab ride away. This is where many of the stone workers live and this is also where the moisture conditions are perfect for aging such works of art.

Kyoto Woodworking Industry

The art of Japanese wood work is widely regarded as the most refined in the world. For example, the sculpture masterpieces of the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) are still considered to be the finest examples of wooden human portraiture in existence. And few wooden structures anywhere can compare to the immensity and graceful perfection epitomized by the temples of the Nara period (710-794). Traditional Japanese woodwork can be broken up into five distinct categories ム carving, joinery, barrel construction, circular wooden containers, and lathe work. Kyoto has craftsmen active in all of these areas. However, most of the industry continues to be centered largely in the hands of individual craftspersons working out of private studios. And, like so many other traditional Japanese industries, the existence of the woodworking industry is under serious threat by modern construction methods. Traditional Japanese woodwork is based on the use of tools which are sharpened to nearly razor blade sharpness by hand, a process that is as demanding as it is time consuming. The time intensive nature of this craft is reflected in the high prices commanded by Japanese wooden hand-crafted things. Nevertheless, creations and objects born from the Japanese woodworking tradition symbolize perfection itself, with a beauty that is lasting and a quality that endures and endures. This will never change.

Jurinsha: Founded by businessman and wood lover, Mr. Kodo Kan, nearly 30 years ago, Jurinsha plays an important role in Kyoto as a supplier of precious woods, and as a creator of fine wooden furniture and objects. In 1987, Jurinsha added a craft juku to teach traditional wood working techniques. Today, with over 25 students, the juku is one of the leading contributors to the world of wood craftsmanship and creation in Kyoto (foreign students welcome). For more information on Jurinsha's activities call 311-1778 (Fax: 321-6556).

A Conversation with Biwa Player, Tomoko Yamauchi

This interview was with Ms. Tomoko Yamauchi, one of Japan’s only living biwa balladeers in the nearly extinct Heike Biwa style. The Heike Biwa balladeers have been orally transmitting a set of roughly 200 tales related to the tragic Heike clan, since the Kamakura period (1185-1333). Together, these tales make up one of Japan’s oldest written historical accounts, known as the Heike Monogatari, or the Tale of the Heike. The stories deal with the short-lived victory and undying valor and tragic nature of the Taira or Heike Clan, who showed great promise when they vanquished their bitter rivals, the Minamoto or Genji Clan, as well as ousting the Fujiwara Clan, who ruled for much of the Heian period. Many of these tales are essentially tragic love affairs and stories of battle or court intrigue that took place during the passionate, yet decadent final stages of the Heian court in Kyoto. The mostly dark mood of the Heike Monogatari is based around the Buddhist doctrine that all human activity is ephemeral and illusory, that the mighty are destined to be destroyed by time, and that nothing, in the end, can save a human life but the grace of the Amida Buddha. The interview took place in Kyoto in August, 1999.

YJPT: How did you get interested in playing the biwa?

TY: I play a kind of music known as Heikyoku, a style of music that was developed to orally tell the Tales of the Heike [Heike Monogatari]. Nowadays, people are only familiar with these tales from reading them in books. Very few people have ever heard them in their original form, which is the Heikyoku ballad style. My teacher, Tateyama Kogo, from Miyagi Prefecture, was one of the last few living teachers of the oral, musical Heikyoku style. In 1974, when I was 23, I read an article about him and decided that I wanted to help. And I say help because at that time my teacher was worried that he wouldn't have any one to pass his knowledge of these nearly 800-year old ballads on to, and that the tradition would disappear.

Because my teacher was very old when I started, we had little time to lose. I trained nearly full-time on weekends for four years. During the week I worked for the Japan's largest telephone company, NTT. The Tales of the Heike consists of more than 200 different stories that are played on the biwa. Those four years were incredibly difficult for me. After Tateyama-sensei passed away, I continued to work hard at playing these songs as he would have wanted me to. I was very lucky to have the understanding of my company for all those years.

YJPT: Are there musical notes for these songs?

TY: Heikyoku is strictly an oral tradition, so there are no notes at all. The entire repertoire resides within the human memory and is passed on from generation to generation. Even though this is true, presently we are mostly using musical arrangements standardized in the Edo period (1600-1868). It is almost unbelievable in this day and age to think that the songs or stories that I am playing have been successfully handed down for nearly 800 years. The music and acting for the Noh and Kyogen theater forms, which developed around the same time as Heikyoku, have been handed down in the same way. I learned a lot about the nuances of my songs by attending Noh plays and listening.

YJPT: What is it that attracts you about the biwa and its music?

TY: When I play, I can feel time slowly slipping away, back to the moods of the Heian and Kamakura periods. In today's mad and modern, high-paced, high-stress lifestyle, escaping into the biwa is precious and relaxing.

When I play, I try very hard to express the essence of a human emotion or the sound of a situation through the instrument. If it is a tragic love story, I try to express the sadness of the woman. If it is an epic battle scene, I try to evoke the sound and feeling of war.

All sound travels through the air to our ears. Therefore, the sound of the biwa is really very different according to the season. This is why I don't make tape. To appreciate the biwa you have to hear it live. There is no other way.

YJPT: What is the history or background of the biwa itself?

TY: The instrument and the basic musical style developed in China, and from there eventually came to Japan. In Japan, four different kinds of biwa music developed. The first kind, the original Chinese style, was used in the Nara [710-794] and Heian [794-1185] periods for gagaku or imperial court music. Another style, known as the Moso biwa style was used by blind monks to "read" Buddhist sutras. The third style, the Heike biwa style, is the one I'm playing. The fourth style is called the Kindai biwa style. Also known as the Satsuma or Chikuzen style. The Satsuma style developed about 300 years ago and was very popular in southern Japan, mainly in Kyushu culture. The Chikuzen style, which grew from the Satsuma style, developed about 100 years ago.

YJPT: How many professional Heike biwa players are there in Japan?

TY: In the whole country there are only two or three professionals, who play regularly and then a handful of amateurs. Kyoto hasn't had a single professional performer since the 1940s. In Kyushu, I have heard that there are still quite a few Moso biwa players.

YJPT: What is the instrument made of?

TY: Biwa is made of very strong, hard wood, usually kuwa [mulberry]. The four strings or gen are made of silk. The sounds of the biwa are very simple and translucent. This kind of music only has five scales.

YJPT: Are there any other musical instruments that are similar to the biwa?

TY: Yes there are. If you trace the instrument in China, you will find it quite similar or related to the Persian udo and also to the Indian sitar. It also resembles the western lute.

YJPT: Are there still people making biwa?

TY: Yes, there are several people in Kyoto who make instruments for imperial court musicians. The imperial gagaku musicians, now live in Tokyo. Since this kind of music has survived for more than 1,000 years, I am sure that there will always be a need for these ancient instruments.

YJPT: What is your concert schedule like?

TY: Even though I live in Tokyo, I often come to play in Kyoto. The city is perfect for the biwa and its music. It is sad now that I am working in Tokyo. It's difficult to feel the same atmosphere there. But I play all over Japan. I will play in Wakayama this month. I especially like playing in the Kansai region, because the Heikyoku songs are all set in this area.

YJPT: Are you also teaching?

TY: Right now I am not. But that is an important future activity that I look forward to. When I retire, I will devote myself to teaching what I know to others. People have told me that it is nearly impossible to discipline young people these days, but I am not worried too much, indeed I am very much looking forward to teaching. I don't want people stereotype young people in some kind of mainly negative way. There are many young people, in any age, who have tremendous spirit and energy.

YJPT: What is it that you miss about Kyoto?

TY: Kyoto is a mature city, full of elegance and history. I guess my favourite place in Kyoto, the place that I miss but which is always in my heart, is Jakko-in Temple in Ohara. This is where the last remaining aristocratic member of the Heike family, Kenrei Monin, retreated to and devoted her life to being a nun. The tragedy of that distant time is still there in the atmosphere of the temple and its surroundings. Others things I love about Kyoto are the hour around sunset, the light is so exquisite, the graceful, green willows along the Kamogawa River, seeing maiko walking along the streets of Gion, and people splashing water on the street [uchimizu] in front of their homes and businesses. Surrounded by mountains, I feel something warm and secure in Kyoto, like she was my mother. I return whenever I can and it always feels like home.

- Kyo Yuzen natural dyeing creates strong beautiful textiles

- The best granite & sand in Japan for gardens

- Kyoto's woodworking industry

- A Conversation with a pro biwa lute musician

- Indexed full list of all my blog posts | articles.

- Indexed full list of all my Japanese culture essays.

Content by Japan travel specialist & designer Ian Martin Ropke, founder & owner of Your Japan Private Tours (YJPT, est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with all of YJPT's Japan private tour clients and have a great team behind me. I promote YJPT through this content and only advertise at www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip to save time & have a better time. Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search) is also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!