Japan August travel seasonal highlights, themes and attractions

August Japan travel falls into three phases, the first two weeks before the Obon, Festival of the Dead, the Obon national holiday period, and, finally, the last 10 days or so of August. The notorious heat and humidity of July continues in August, so you have to get out early, take an afternoon siesta break, and then enjoy the falling temperatures from about 16:30 or so . . . And since school is out in Japan for the entire month of August you can expect domestic tourists pretty much everywhere you go. But during Obon you will find Tokyo to be “almost empty” as everyone has returned to their hometowns.

At the same time, August in Japan is super popular with Europeans and a lot of Southeast Asians. So, when you combine the heat, the Buddhist Obon festivities (which last about a week) and the popularity of the season it’s important to choose wisely. Big Japanese cities will be fairly quiet in August, but you will find plenty of people on the best beaches and in the cool worlds of the mountains. And Hokkaido, of all the islands, is very busy in August. So, lots of choices and things to consider.

It is also important to note and mentally prepare yourself for the high possibility of powerful typhoons or hurricanes in August. Normally, typhoons come in the middle of August and hurricane season usually ends in mid-September. However, climate change has changed this pattern quite a bit: pushing typhoons into early August in some years; and also, the strength and frequency of typhoons, overall, have increased over the past 30 years. Typhoons can be challenging but usually only at sea level and in “more or less” well-known coastal areas, but these do include Osaka, Nagoya, Tokyo and Hiroshima, parts of Kyushu and a lot of Shikoku. So do pay attention to the weather forecasts from time to time.

August days in Japan begin with the sweet sounds of early birds. That usually lasts until about eight or so. From then to sunset there is only one sound that dominates, no matter where you might be: the endless droning call of the cicada or semi, as they are known in Japan. Japan is home to 35 cicada species. Among insects, semi certainly lead an unusual life. They spend the first two to six years of their life underground in total darkness and don’t make a sound. And then for a few short weeks in summer they burst out in ear deafening song, search out a mate, procreate, and suddenly fall dead in incredible numbers as September draws to a close. In the Japanese poetry of the Nara (710-794) and Heian (794-1185) periods, semi were symbolic of the early beginnings of the autumn season, solitude, melancholy, and the fleeting nature of life. But by the Edo period (1600-1868) the cicada had become what it is today: a noisy and loved symbol of summer!

Japan’s unique Obon Festival, an ancient religious rite to honor the souls of one’s dead ancestors, is held throughout Japan. Obon celebrations usually begin in Hokkaido (north Japan) and end in Kyushu and Okinawa (south Japan). In Kyoto, most of the main public and family Obon rituals take place between the 14th and the 16th. During this somewhat solemn holiday, people from all over the country journey back to their furosato (hometown) for the second major family reunion of the year (the first being during the New Year holiday). Obon is also a long holiday which marks the end of the Japanese summer. In many places, thousands of candles are lit in cemeteries or in paper lanterns that are floated out to sea on the local river or stream. Kyoto is the only city that has the giant send-off bonfires known as okuribi, but Nara has something similar.

Traditionally the passing of obon (mid-August) marks the end of summer. One of these is swimming. In old Japan and even today many people believed that the ghosts of unhappy ancestors remained caught in the water worlds. In fact, Japan has long been “alive” with superstitions and stories of ghosts. In the late Edo Period ghost stories were so popular that professional storytellers included the hyaku monogatari (One Hundred Supernatural Tales) in their repertoires. See the section below, just before the August temple head interview, for more on Japanese superstitions and ghosts.

In the Japanese tea ceremony, the month of August has been poetically captured with “goma” associations that capture the essence of each 10-day period: early August, mid-August, late August. These key words and themes that have been classically repeated in Japan for more than 1,200 years. The August goma key words can help you “imagine” what to expect when you travel in Japan in that month. Early August themes: Hanabi fireworks. Yoi Suzushi cool evenings, evening coolness. Mid-August themes: Toro Nagashi floating lanterns used in the Obon festival to send off the spirits of ancestors; the lighted lanterns are floated down the river to the ocean). Semi cicadas and the cast-off shell of cicada (a symbol the briefness of life). Late August themes: Hatsu Arashi first typhoons of autumn. Mushi no Ne autumn insect chirping.

- Japan August travel food highlights

- Japan August travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan August travel festival highlights

- Festival Of The Dead: August Buddhist shopping

- Late August is superstition and ghost time in Japan!

- August Interview With The Head Monk Of Kyoto’s Kurodani Temple

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!

Japan August travel food highlights

River Eel Unagi cuisine: Unagi or eel is a great traditional way to gain energy on hot summer days. The eels are grilled and basted over hot charcoals (oak is the best!). Every restaurant has its own special basting sauce recipe. The best eels are caught wild in rivers and kept in tanks. When your eel dish arrives, season lightly with sansho (green Japanese pepper). Recommended dishes: Unagi Donburi: Eel broiled over charcoal and basted with soy-sauce and a sweet-saké based sauce. Served on top of rice in square boxes. Unagi Kaba-yaki: Kaba-yaki consists of whole eel served on a long plate, with rice and soup served separately. Generally, the amount of eel is more than what would get with the donburi version above. (In Kyoto this dish is also called mamushi, which is the name of a fairly common poisonous snake, normally found in rice paddies.). Uzaku: This refreshing dish consists of broiled eel cut into small pieces mixed with cucumber slices, to which a little vinegar and soy sauce is added.

Traditional summer desserts: Some of my favorite summertime sweets this month: mizu botan is white and colored pink wrapped in a kudzu gelatin which is then steamed (manju) to create a delightful transparent summer sweet. Kayoiji is rakugan (rice flour cake) with Daitoku-ji natto beans sprinkled here and there to suggest steppingstones. The sweet rice cake with the salty natto is a good combination of flavors. I also like the mizu yokan that is poured into small green bamboo tubes when hot and allowed to cool. You poke a hole in the bottom of the bamboo and suck the sweet out of the tube — very refreshing.

Modern Japanese summer desserts: The modern dessert worlds of Japan are hugely popular with modern-day Japanese people and foreign tourists. And there is always something new when you walk around Shibuya in Tokyo or the busiest tourist areas of Kyoto and Nara. There is matcha green tea ice cream, matcha smoothies, handmade ice creams (with unusual flavors like sweet potato). Domestic Japanese ice cream brands sell like crazy in summer alongside multinationals such as Haagen-Dazs. But the most innovative flavors are being created by artisanal businesses. A good number of these craft ice cream companies are concentrated in the historic town of Kanazawa, in Ishikawa prefecture. It is even known as the "Japan's ice cream capital!!!"

Japan August travel tree and flower highlights

The Lotus Flower: The lotus (hasu) flower springs forth out of muddy pond waters to show large pink or white flowers for about four days in the intense July heat. The flowers open at dawn and close by mid-afternoon. Its short-lived blossom suggests reincarnation; the wheel-like leaves and spike-shaped petals imply the perpetual cycle of existence; and the pure flowers rising from the mud symbolize enlightenment for anyone. Lotus seeds are often used as Buddhist rosary beads. Even after blooming, the lotus is beautiful. The seed pod has a distinctive, honeycomb shape, while the large leaves retain their deep green. The roots (renkon) are edible and are used in numerous Japanese dishes.

Hydrangea ajisai: Hydrangea begin flowering in June and can be experienced all over Japan in July (until about mid-July at sea level and later higher up in the mountains). The most famous locations are Yatadera Temple, Nara; and Hasedera Temple, Kamakura.

Morning Glory Asagao: Morning Glories or Asagao bloom throughout July and August and are the favourite display flower in the front gardens of traditional homes and at major botanical gardens all over the country. In particular, the area of Iriya in Tokyo is very famous for its floral markets. Every year in July, there is an open market with nearly 100 flower shops known as the Iriya Morning Glory Festival (first week in July) at Iriya Kishimojin temple that attracts about 400,000 visitors over the weekend, who come to admire and buy morning glories. It starts early in the morning so that you can see the morning glories fresh and in full bloom.

Sunflowers: Sunflowers are hugely popular in Japan and can be seen in a few places around Tokyo and, best of all, in Hokkaido. The big field venues for sunflowers are the Hokuryu Sunflower Village (Hokkaido); Kiyose Sunflower Festival (Tokyo); and the Yamanakako Hanano Miyako Park (Mount Fuji, Yamanashi prefecture).

Furano flower fields (Hokkaido): Hokkaido and its enormous wide open spaces is super famous in summer in general and for its flowers in spring, summer and autumn. No place is more famous and more posted on Instagram than the Furano flower fields.

- Japan August travel food highlights

- Japan August travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan August travel festival highlights

- Festival Of The Dead: August Buddhist shopping

- Late August is superstition and ghost time in Japan!

- August Interview With The Head Monk Of Kyoto’s Kurodani Temple

Japan August travel festival highlights

Morioka Sansa Odori (August 1-4; Morioka): A taiko drum festival featuring the Sansa dance of Tohoku. It's big and it's pounding. The largest taiko drum event in the world. Aomori Nebuta Festival (August 2-7; Aomori): The Aomori Nebuta Festival is a paper lantern festival that achieves stunning visual effects. Cold northern communities love the summer. Summer festivals in Tohoku have a special kind of intensity. Kanto Festival (August 3-6; Akita): The people of Akita prefecture in Tohoku have found a unique way to scare devils away from Autumn crops by balancing 12-meter bamboo poles with up to 46 lit lanterns on them. The Kanto Matsuri is an impressive display that attracts over a million celebrants to Akita in early August. Gojo Pottery Festival (August 7-10; Kyoto): As part of the preparations for Obon, families throughout the country replace the ceramic dishes used on the ancestral altar with new ones. This yearly activity is what got Kyoto’s Toki Matsuri festival started. During, this massive outdoor ceramic event, people come to buy new offering plates and dishes for the home and often for family graves as well. Thousands of others come simply to look for bargains and take part in the fun. You are sure to find something worth buying at this sale. Even if you don’t find something, it is a great opportunity to watch people and sense the coming days of Obon. Super Firework Events (early August before Obon; various locations): Hanabi, or "fire flowers", have traditionally been and continue to be everyone's favorite diversion on hot and lazy August nights. And the Kansai region has a number of big fireworks displays that draw huge number of spectators. Fireworks and firearms were introduced to Japan by the Portuguese in the late 16th century. The Japanese became masters of the art of firework design. Biwako Hanabi Daikai (8/8): from 19:30 to about 21:00, in the vicinity of Niono-hama Beach. Free. Access: From JR Kyoto Station, take the Biwako Line to either Otsu or Zeze Station (about a 15-minute ride). Don't drive - the roads are too crowded! Uji River Fireworks Display (8/10): At 19:30, 7,000 fireworks will be set off over the Uji River. Before the display there will be outdoor music performances. To get there (and get there early) take the JR Nara line to Uji or the Keihan line (change at Chushojima!) to Uji. Enryaku-ji Temple Special Night Ceremony (August 9-11; Kyoto): For these 3 days, the entire eastern part of Enryaku-ji Temple is unforgettably illuminated with more than 2,000 Japanese lanterns. Music concerts on a special stage and night ceremonies will also take place at Konpo-chudo (the main hall). Special shuttle buses will run from Keihan Sanjo Stn. to take people to the Enryakuji night ceremony (the ride takes about 30 min.). Tokushima Awa Odori (August 12-15, Tokushima): The people of Tokushima are so proud of their August dance festival that they named their airport after it. It's Japan's best festival. Arashiyama Summer Night Festival (8/23-27): This popular, large Kyoto summer festival (in Arashiyama) features many interesting events, including an Ukai (cormorant fishing) show, professional Bon Odori dancing and singing, and a yukata (cotton summer kimono) contest. Yukata will be lent out (for free) during festival. Tel: 752-0227. Cormorant Fishing (all of August; various locations): Gazing across the river, glowing red from the torch lights of the old fishing boats, you'll hear the echoing voices of fishermen trying to catch ayu (sweet fish) in the darkness of the night. But they are not using poles. Dressed in traditional head gear with aprons made of straw, each fisherman skillfully controls the six cormorants tied to his boat to catch fish for him. This unique and traditional way of fishing, which is known as ukai in Japanese, originated in the 8th century. Today, it remains little more than an exotic tourist attraction in various places in Japan, especially in Kyoto but also in Uji and elsewhere. Fukagawa Hachiman (late August; Tokyo): A massive summer mikoshi festival in the Fukagawa area of Tokyo. A total of 54 mikoshi teams compete to be the most energetic tossing 2000-kilogram mikoshi in the air while the volunteer fire department sprays them with a full pressure fire hose. It's a rare water fight in the Tokyo August heat.

- Japan August travel food highlights

- Japan August travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan August travel festival highlights

- Festival Of The Dead: August Buddhist shopping

- Late August is superstition and ghost time in Japan!

- August Interview With The Head Monk Of Kyoto’s Kurodani Temple

Festival Of The Dead: August Buddhist shopping

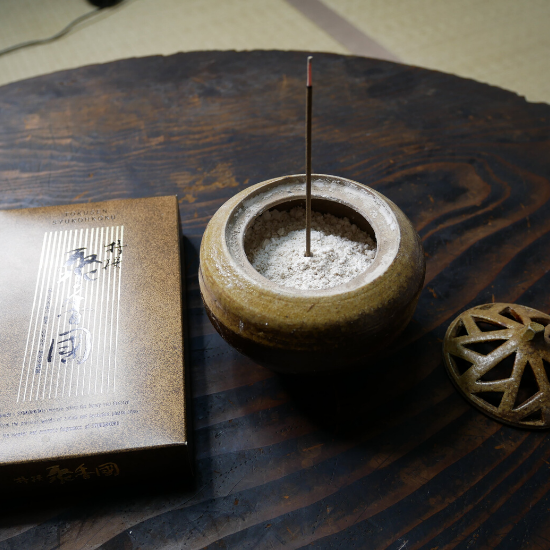

Incense, candles and juzu rosary beads are all part of the daily world of the devoted Buddhist. They are also things that can lead to a simpler, more spiritual and quieter life. And they are prominent display and in use all over Japan during the Obon Festival of the Dead period.

Incense:Kyoto is the best place to buy Japanese incense, probably the finest in the world. Incense sticks are used in temples, in front of graves, and on the family alter, but can also be used in a more general spiritual way in your home. In recent years the use of senko (or oko), as a way to reduce stress and enter a quieter more spiritual space, has made a considerable comeback. The best incense is made from 100% natural materials and has a sophistication that is beyond words. It is subtle to the point of surprise and has the unique effect of calming a busy mind, the frantic heart, and leading the confused soul to sweeter, simpler lands.

Candles:Traditional Japanese candles are rare nowadays. Tanji Rensho-do (northwest of Kyoto Sta) is one of the few traditional candle-making shops left. Their candles are made of an exceptionally pure wax derived from the fruit of a kind of sumac. Unlike beeswax candles, sumac candles do not drip or smoke when burned. If you are in this area, take the time to pick up a few real, old-style candles. Excellent candles are also sold at Kyoto’s monthly outdoor markets.

Juzu:Juzu, a special kind of beaded necklace or bracelet rosary, is an extremely popular item in the Buddhist worlds of Japan. The beads used to make juzu are fashioned from a number of different materials including nuts, precious woods (lime and sandalwood), semi precious stones, crystal and agate. Full length juzu are made of 108 beads, for the 108 different human desires. By wearing and praying with juzu, Buddhists are able to rid themselves of worldly passions in order to become more benevolent and virtuous.

Late August is superstition and ghost time in Japan!

More Japanese people believe in old superstitions more than you might think. Every country or culture has its own superstitions. Sometimes the symbol of fortune or a sacred object in one country has a completely different meaning in other cultures. For example, Japanese think that if a bird poops on you that it is a good luck sign. A European would never think of that as a good sign. Another example is snakeskin. Some Japanese people put pieces of a shed snakeskin in their wallet in the belief their money will return the way a snake’s new skin returns.

One superstitious thing many Japanese people are really careful about is yakudoshi or misfortune/bad luck years. There are three different ages in one’s life that are believed to be particularly bad for unfortunate incidents or events: 25, 42, and 61 for men, and 19, 33, and 37 for women. The year before and after these ages are also part of the bad luck cycle. The middle year, called taiyaku (big misfortune), is the worst. Japanese people visit shrines to pray to the gods to rid them of bad events (yakuyoke). Some shrines hold special rituals for yakuyoke. Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto offers this service (on most days) from 9:00 to 16:00 for Yen 5,000.

Another way to stop the bad energy of yakudoshi is to carry something that has seven special colors (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, navy blue and purple). Belts, wallets, bracelets and pendants are among the things one can find in Japan with these 7 colors. Recently, 7-color straps for cell phones have become very popular.

Some locations are more alive with superstition and power than others. One of the most famous in Kyoto is Ichijo Modori-bashi Bridge, where the dead come back (modoru) to life. In the early Heian period (794-1132), a monk named Jozo was training deep in the mountains. One day he got a letter that said his father was in critical condition. He tried to return quickly to Kyoto to speak with him one last time. However, he arrived only to see the funeral crossing over the bridge. Jozo prayed strongly that his father would come to life so that they could speak again. Suddenly the sky above the bridge became dark, a bolt of lightning struck, and his father revived. This is how the bridge got its name. In World War II, many Japanese soldiers came to this bridge in the belief that they could come back from the death fields of war. Engaged women are warned not to cross the bridge as it may turn her into an unengaged woman again.

Another legend related to this bridge is about Abe no Seimei, the most famous sorcerer of the Heian period (794-1185). According to one story, he hid his magical power or shikigami under the bridge. Therefore, the bridge is believed to have some mysterious power from him. Abe no Seimei is still very famous and there is a number of books and information about to him. Seimei Shrine, a 5-min. walk north of Ichijo Modoribashi bridge, enshrines his spirit. Many people from all over Japan come and visit here every day.

Japan is also alive with superstitions and stories of ghosts. For example, many people believe that the ghosts of unhappy ancestors remain caught in the water worlds after Obon (August 10-16) and so many stop swimming after August 16th.

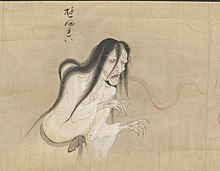

In the Edo period (1600-1867) telling ghost stories was a popular nighttime fright game in which groups of people would gather at night and lit one hundred candles, taking turns telling ghost stories. For each tale told a candle was extinguished, deepening the shadows and the tension until the room was plunged into darkness—ghosts would then appear!

Yurei, usually the ghosts of females who died in the grip of intense emotions such as jealousy or despair, are considered to be the most terrible ghosts. They are depicted as a shadowy figure draped in a white burial kimono; hands are limp and beckoning, hair long and messy.

A well-known yurei tale is about Oiwa and her husband, Iyemon, who betrays her. But when Iyemon tries to poison Oiwa, he only disfigures her, leaving one eye bulging from a swollen, partly bald head. Finally, he impales Oiwa and her servant to a door and throws them into a river. Thinking his troubles are over, he marries. When he lifts his bride's wedding veil he is terrified to see the vengeful face of Oiwa’s ghost. Drawing his sword, he mistakenly beheads his new bride!

- Japan August travel food highlights

- Japan August travel tree and flower highlights

- Japan August travel festival highlights

- Festival Of The Dead: August Buddhist shopping

- Late August is superstition and ghost time in Japan!

- August Interview With The Head Monk Of Kyoto’s Kurodani Temple

August Interview With The Head Monk Of Kyoto’s Kurodani Temple

This interview with Ryu-gen Ieda, Head Steward of Kurodani Temple, took place in August 2000. Also known as Konkai Komyo-ji Temple, Kurodani Temple is Kyoto’s second most prestigious Jodo (Pure Land) sect temples after Chion-in Temple. Honen, the founder of the Pure Land sect, was wandering on the slopes of the “Kurodani hills,” when he found a large stone and sat down there. Then a purple cloud rose from the stone, covered the sky, and a golden light was cast over the western sky. Seeing all this, Honen built a thatched hut there. The stone is still there!

YJPT:How did you become a monk?

Ieda-san:Well, strange as it may seem, I was born to be a monk because my father was a monk. Born and raised in a temple, I spent the first years of my life in Matsumoto in Nagano Prefecture. The name of our temple was Keirin or “Happy Forest”. We moved to Saiun-in, here in Kurodani Temple, when I was five.

The head of Saiun-in at that time had been one of my father’s teachers and, though he had several students, he was particularly fond of my father. So, before he passed away, he asked my father to take over.

YJPT:How would you compare your life as a young man to that of today’s young?

Ieda-san:I think it is incomparable. I got my red paper, on which the government had printed its order that I had to become a soldier and go to war, in June of 1945. We were losing pretty badly by that time and so the government was running out of 20-year-olds and had to start drafting 19-year-olds. I went of course. One really didn’t have a choice. But I didn’t like being soldier. Many people said that I should try to become an officer. Being an officer was naturally seen to be better since you didn’t have to kill anyone with your own hands. You just had to give the order for someone else to do the killing. But I didn’t think that way. I thought if there are no choices, then I’d rather be a soldier. Nothing seemed worse to me than giving other people the order to kill people. As a normal soldier, I resisted as much as I could and drove my commanding officers quite crazy.

In my generation there was always war and we had no time to say what we wanted or do what we wanted. There was a distinct lack of freedom that young people today take for granted. These days, when I look at young Japanese people, I feel that I am looking at Americans. But the difference is that Americans take or are taught to take responsibility for their actions. Young Japanese people don’t. In Japan freedom means freedom without responsibility and this causes a lot of problems.

Younger people need to learn how to think for themselves. Japan has always been a culture that believed that strict discipline would teach people how to think and do things right. But I never thought that was the right way. We need to learn right and wrong through our individual experience and we need to understand that our actions effect everyone.

YJPT:Do you have any schools here at the temple?

Ieda-san:The Jodo sect, which is Japan’s second largest Buddhist religion, has many kinds of schools: everything from kindergarten to university. But here at Kurodani, we only have a kindergarten. All children are welcome, but we do insist on teaching the essential basics of Buddhism.

However, I also run my own kindergarten outside of the temple. And I run this school quite differently from most kindergartens. At our school, we try to teach the children as little as possible. I think it is very important for children to become who they are naturally, not with a lot of discipline and instruction. I want our students to discover the eternal circle of life on their own. We do not give them a lot of orders. Instead, we treat the students and teachers as equals and try to learn from each other. When the students first come to the kindergarten some of them don’t know how to play, but we try not to tell them how to play. We only prepare the accessories and facilities for play and keep an eye on them. The kids seem to prefer this.

Over the years I have studied my different kinds of education. I remember when I visited a school in the USA., that one of the American teachers said that they didn’t like Japanese education and educators. I asked him why he felt that way, and he said that Japanese educators simply look for models that they can copy. He said that everyone and every society has to find its own way to teach people. I agree with him, but I have not found it easy to introduce change into the education system here. It is amazing how rigid many parents are.

YJPT:Many countries teach people about math, history, literature and so on. Why don’t schools teach people about spiritual matters? Isn’t that what Buddhism is all about?

Ieda-san:Well Japanese monks and temples, at least until the end of the Edo period (1603-1868), were responsible for instructing the common people in these matters. But when Japan opened her doors to the West, Buddhism suddenly ceased to be recognized as an official Japanese religion. Monks had to choose between the new rules and destroying their temples. Basically, the government ordered all monks to begin eating meat, to let their hair grow and get married. And yet the only people qualified to teach people about spiritual matters in Japanese society were monks.

So when the government destroyed Buddhism they destroyed the spiritual educational basis of the country. For the first sixty or seventy years after Buddhism was destroyed, many of the basic teaching were passed on from parent to child. But today many parents no longer know what is right and wrong. Many people have forgotten the essentials ways of spiritual life. This has had an immense influence on modern Japanese society.

YJPT:Do you think Japan’s future will be difficult?

Ieda-san:I don’t think so. We are a resourceful, skillful people and, as a country, we are quite rich. But at the same time, I feel this last long economic depression was very good for people. After losing the war, we have not really had an opportunity to reflect on our past. The government wanted us not to think, but to work as hard as possible. We have never collectively faced the darkness of our own history. And yet only by facing and fully accepting the dark side of our history can we expect to grow in a positive and enlightening manner.

YJPT:Japanese people never seem to praise each other in the family, at school or at work. Why is that?

Ieda-san:It must be sad for you to see our way. One might explain this by saying that the Japanese are extremely shy by nature. Praise and criticism are both important in my opinion. Another way to explain this lack of praise in Japan is to agree that most people nowadays have too much knowledge, they study too much. And because of that we are emotionally poor. We really have to start learning how to build our own life and thinking in our own way. And we have to stop thinking that money is the answer to everything.

The Buddha never had any money or possessions. He just had his robe, a food bowl and a walking stick. Monks in Myanmar are still like that. They seem to have nothing. Rich people are always thinking about how to protect their property. They are too busy protecting everything.

We have to learn to be more humble and simpler. We need to understand that an unseen power exists in the universe. Many people do not believe in these things. But the universe is immense and there are so many things that we don’t know. We are so insignificant on the true scale of life. We need to stop fighting and arguing. So many people are starving. We need to find some way beyond the immense contradictions in our life.

YJPT:As a final question, what are your favorite things in life, your favorite places in Kyoto?

Ieda-san:When I was young, I used to visit many places. But these days, I don’t go out very often. I have an old friend, my dog, and we walk together in the grounds of the temple together. I love all plants and animals and I give thanks for their presence every day. I also feed the crows and other birds every day with old fruit in my courtyard. This makes me happy.

And I love cleaning up the fallen leaves. In the old days we had lots of student monks to help clean up the grounds. But now many monks in large temples plant evergreen trees so that they don’t have to clean up the fallen leaves. I think it is a damn shame that we have become so practical. Fallen leaves remind us of the great circle of life and death, of the seasons, of the short time that we have to live.

Japan month by month private travel & culture summary index

Japan spring travel: Mar, April, May. Learn more!

Japan summer travel: June, July, August. Learn more!

Japan autumn travel: Sept, Oct, Nov. Learn more!

Japan winter travel: Dec, Jan, Feb. Learn more!

Content by Ian Martin Ropke, owner of Your Japan Private Tours (est. 1990). I have been planning, designing, and making custom Japan private tours on all five Japanese islands since the early 1990s. I work closely with Japan private tour clients and have worked for all kinds of families, companies, and individuals since 1990. Clients find me mostly via organic search, and I advertise my custom Japan private tours & travel services on www.japan-guide.com, which has the best all-Japan English content & maps in Japan! If you are going to Japan and you understand the advantages of private travel, consider my services for your next trip. And thank you for reading my content. I, Ian Martin Ropke (unique on Google Search), am also a serious nonfiction and fiction writer, a startup founder (NexussPlus.com), and a spiritual wood sculptor. Learn more!